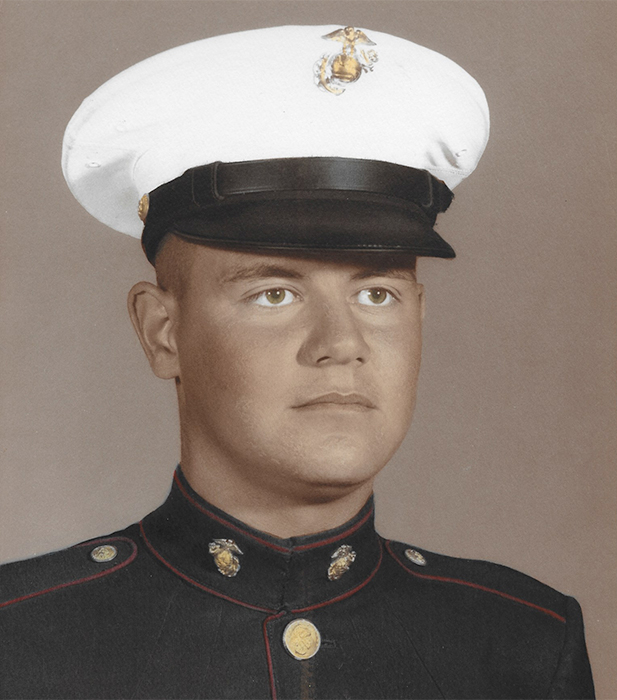

Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, and his son pose for a picture.

Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, and his son pose for a picture.More Than a Game Season 2, Episode 8

Rudy Gallego recently became the first adaptive athlete to have a jersey retired at the University of Arizona. Gallego is a local legend for starting the university's wheelchair basketball team, beginning what would grow into an adaptive sports program with more than 50 Paralympian alumni.

Episode Transcript:

[Music]

Tony Perkins: I'm Tony Perkins. And this is More Than a Game, the podcast that takes you beyond the box score, and tells the Arizona sports stories you never heard. On this episode, we learn about an early pioneer in adaptive sport.

50 years have passed since the University of Arizona first ventured into wheelchair basketball. Today, the adaptive sports program stands as one of the nation's finest, boasting a roster of 63 competitive disabled student athletes and more than 50 Paralympian alumni. But before that success came a trailblazer who laid the foundation for it all. Rudy Gallegos name is not as widely recognized as other you obey athletics grades. Yet his contribution to the world of adaptive athletics is nothing short of legendary. In a time, when the notion of disabled athletes competing was put to the sidelines, Rudy pioneered a movement that would change the landscape of adaptive athletics and Tucson forever. Paola Rodriguez tells us the story of this one unsung hero from a land mine accident

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, is on the court during a UA wheelchair basketball game.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, is on the court during a UA wheelchair basketball game. Paola Rodriguez: When you describe Rudy to someone who doesn't know him, how would you describe him?

Andy Morales: Funny, humorous, don't take it take him too seriously because his joking might come off as teasing to some. And just go with the flow and and be a part of it and and he'll become your friend quickly. He'll joke about his disability. It's okay to laugh about it with him. That's how I would describe it. And and friend.

PR: Longtime sports writer and coach Andy Morales first met his friend Rudy Gallego, when he began an internship with former adaptive Athletics Director Dave Herr-Cardillio coaching wheelchair athletes.

AM: Well, he was this strange guy in a wheelchair. I mean, he was missing fingers. Obviously, you notice all that stuff right away. And he was chucking up these three-point shots. Swish, swish, swish. So my first impression was he was an athlete. And then my next impression was, well, there's something else going on here because he would, he would yell weird stuff like "touchdown", "Pueblo" every time he made a basket and I'm like, what, what's going on here? But he just had a lot of stuff he had to work through, I guess.

PR: Born in 1949. Rudy never expected to live the life he did, becoming an all-star athlete at Pueblo High School. His passion for sports superseded most things in his life, as his wife, Sherry, would say,

Sherry Gallego: And he put his heart and soul into wheelchair basketball. And supposedly the baseball even came before me. So but I said, that's cool. I understand. I'm okay with that. You know, I'm not the jealous type.

PR: I was gonna ask where you ranked in all of that.

SG: Yeah. I'm not sure. It's one of those things you really don't want to ask. You might not like what you hear.

PR: Ignorance is bliss. Rudy's first love was baseball, and was even recruited to play for the St. Louis Cardinals. But upon the advisement of his friends, Gallego declined the team's offer after spring training, and went to college to gain more experience. Soon after just a semester at school, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. On June 9 of 1970, his life changed forever. However, Rudy liked to tell a different story from what actually happened.

AM: He used to tell me that he had his injuries by jumping on a grenade. And I believed that for like 10 years, and then someone said he'd never jumped on a grenade.

PR: In reality, Rudy stepped on a landmine during the Vietnam War, effectively ending his professional baseball dream. The impact left him as a double amputee along with the loss of his index and middle fingers.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program Rudy Gallego poses for his United States Marine Corps headshot.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program Rudy Gallego poses for his United States Marine Corps headshot. SG: Because everyone says that when he stepped on a landmine by right he should have died. That's what that's when Rudy should have died, he should have died then but for some reason, you know, he lived. God chose that he had other things in life for for him to do and he just ran with that.

PR: What would have been considered by many a soul-crushing life-ending moment, Rudy adapted to his new reality. After realizing he wouldn't be able to go back to his baseball dreams, Rudy found new ways to keep sports in his life.

RG: He poured his heart and soul into the wheelchair basketball. We used to chase down cars with wheelchairs in them just to recruit the players. And, you know, if he saw someone with a limp that was six foot two, he would get, like really excited because wheelchair basketball players aren't really that that tall, you know.

PR: Rudy would go on to start the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program. And as his son, also named Rudy, would say, go to any lengths to build a team.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, poses for a photo with a little league baseball team he coached.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, poses for a photo with a little league baseball team he coached. RG: One of his biggest things back then was there used to be an Arizona Daily Wildcat and they put an ad interested in wheelchair basketball, looking for people to play. They were getting people that were blind, one arm, no arms. He was getting all these people with different disabilities.

PR: The program would eventually recruit enough players and become a community-based team, including many players that weren't students. At the time, the younger Rudy said many viewed the program apprehensively.

RG: You know, people that don't associate with someone in a wheelchair or disability every day, like they're in awe, and they're like, oh, wow, like, I didn't know they could do that.

PR: Sherry says that would change over time.

SG: Other people they probably were a little it was like, they probably thought, what? this is kind of weird, you know. But as as the program grew, and they did more, they got more and more people got more and more involved.

PR: With support the program later drew in crowds and competed across the country. Quickly, new traditions began and they were off to the races. Tournaments, like Lame for a Game--an exhibition where both the men's and women's varsity basketball teams compete in sports wheelchairs against the University of Arizona wildchairs--brought in never-before-seen crowds to wheelchair basketball games. Like in 1997, when the NCAA national basketball champions competed against the wildchairs in the 14th annual Lame for a Game before a sellout crowd of 14,000 fans at McKale Memorial Center. The younger Rudy says the exhibition was more than just playing the game. It was a chance to show off their athleticism.

RG: We're still athletes, we can do what you can do. We just can't do it above the rim like you can. But the rim is the same size but we can't dunk it. We can't even leave our chairs or your you know, your your rear end has to stay on the seat. A lot of guys strap in. Even if we fall over, we're still going to be able to get up on our by ourselves. Because if you can't get up in a wheelchair, then you can be part of the play.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, poses for a picture with a community wheelchair basketball team.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, poses for a picture with a community wheelchair basketball team. PR: Over the course of Rudy's athletic career, he found his love for the sport growing in new ways, like coaching.

SG: If somebody was interested in learning, Rudy could you know he would he would spend hours and hours teaching them what you know about learning about this basketball, baseball,

PR: Rudy became the head coach for the program and connected young athletes to wheelchair sports, even going as far as to coach able-bodied athletes in Little League baseball.

RG: Yeah. And he coached soccer as well. I learned how to kick from the other coach, though. But my dad was really fundamental. And like everything that he did, like he could explain it, he'd get down on his hands and knees, he'd move your feet the way you needed to move it if he needed to adjust you.

PR: However, the younger Rudy would say, his dad wasn't an easy coach.

RG: You know, they'd let me shoot the ball. If I needed to. Him on the other hand, he's like, nope, come and rip it away from me, block the shot. And he's like, I'm not giving you any slack because there's going to be one day where I'm not going to be able to do this and you're, you're gonna, you're gonna be you'll be fine. But you're not getting any free passes from me.

PR: The tables would later turn for Rudy and his son when he got the opportunity to play side by side with his dad over the course of 10 games.

VIEW LARGER Former University of Arizona wheelchair basketball player and founder Rudy Gallego plays tennis.

VIEW LARGER Former University of Arizona wheelchair basketball player and founder Rudy Gallego plays tennis. RG: I told myself I wouldn't do this. There was a basketball tournament in Houston, Texas. And it was his idea, and they allowed one able-bodied person to get in a wheelchair and play. And he was like, Hey, we could go to Houston and we can play, you could play and I'm like, let's do this. I got to play with him as a teammate, and a competitor. And it was basically, it was something I always wanted, right? Like I would I would think of scenarios and I know this is funny. I don't know if I've ever said this but of ways that I could like injure my foot so that I could play wheelchair basketball because like for me to play wheelchair basketball was like, because I wanted to be like him.

PR: They didn't win that tournament. But the younger Rudy won something much greater than a trophy, time with his dad, doing what they both loved the most.

RG: He won't admit this or whatever. But he ended up with, like, 36 points. And I ended up with 32. And he's like, I had more points than you and I didn't even play as long as you, right? And he just to remind me, you know, like, Hey, man, I can still play this game. We ended up we didn't win that day, but probably, of all the accomplishments that I had in sports or whatever, that was probably my best.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball, Rudy Gallego, poses for a picture with the little league baseball team he coached.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball, Rudy Gallego, poses for a picture with the little league baseball team he coached. PR: Rudy was a team player. Through death, his family would say, he was known for his dedication and love for his family, his love for sports, and his special ability to influence and coach anyone who is willing to listen and learn.

RG: By far, didn't really care about the wins and losses, he just cared about the success of the people that he played with. Because he was, he was going to be successful. And if he put somebody in a position for them to be successful, he was okay with them being the hero.

PR: The younger Rudy would say his dad was a humble man. And to be honest, he might not have wanted this episode to happen.

SG: He didn't like the spotlight. But deep down inside he did.

PR: So outwardly, you'd be like, I hate this episode. Inwardly he would like I kind of love it.

RG: Yeah. And in his own mind, he's thinking to himself, I'm Rudy Gallego. I'm one of the greatest.

SG: One of the greatest, that's what he always said, he always would say Rudy Gallego, one of the greatest.

RG: Even probably saying the chant Rudy Rudy in his mind as he is going through it you know. That’s just how he was. Never, never, he never would speak it or be verbal about it, but deep down inside you, you know, he, he knew he was good at what he did. And he enjoyed every minute of it.”

PR: Rudy passed away in November last year at the age of 74. However, his legacy now lives forever in the university's adaptive athletics program. In March, the program retired its first jersey in honor of one of the greatest. Shortly after Adaptive Athletics inducted him into the Hall of Fame. For the current adaptive Athletics Director, Peter Hughes, it was important for him to remember the change makers and trailblazers who laid the foundations for the program to become what it is now.

VIEW LARGER Rudy Gallego's son, also named Rudy, daughter Angela, and wife Sherry pose next to his jersey after the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program retired it.

VIEW LARGER Rudy Gallego's son, also named Rudy, daughter Angela, and wife Sherry pose next to his jersey after the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program retired it. Peter Hughes: You know, there were individuals like Rudy that had to advocate for a program here at the university. University didn't have to do that. They did it because it was the right thing to do. But without guys like Rudy and Kent, and you know, Dave Herr-Cardillo, those guys that advocated and kind of shouted, stood up on top of their chair and shouted a little bit saying, hey, this the right thing to do, you know, that the fact that they had that without the protections of, you know, the protections that I've had, which are the ADA and you know, that that kind of stuff that was kind of like, hey, there has to be some sort of opportunity for people with disability. Those guys did it without all that without all that. And, you know, I'll be forever grateful for that fight.

PR: Now, Rudy will forever be remembered as one of the greatest.

RG: It's cool to say like, you know, hey, Pops, you're a Hall of Famer, you know, you know, and his jersey was the first one retired, you know, in that program, you know, well deserved because he was one of the first ones to put on a jersey.

PR: For More Than a Game. I'm Paola Rodriguez.

TP: And that's it for this season of More Than a Game. The show was produced and mixed by Zac Ziegler. Our news director is Christopher Conover. Our logo was designed by AC Swedbergh. Thanks to our marketing team for their help in launching this podcast. This show is part of the AZPM podcast family. You can find all of our podcasts, news and video production at azpm.org. I'm Tony Perkins. Thanks for joining us this season. See you next time.

Nicole Cox: AZPM podcasts are made possible in part by donations from listeners like you learn more at support.azpm.org Thank you

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, poses with his teammates.

VIEW LARGER Founder of the University of Arizona's wheelchair basketball program, Rudy Gallego, poses with his teammates.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.